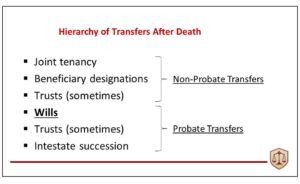

Probate is the state-sponsored process of transferring the assets owned by an individual at death to the rightful recipients. Whether or not a loved one’s assets need to be probated depends on how he or she held title to them and the overall value of the assets.

Probate is not required for assets that have (a) joint tenant owners (e.g. a house), (b) beneficiary designations (e.g. a life insurance policy or retirement plan), or (c) a trust as owner of record. The value of a probate estate excludes non-probate assets.

When probate is required, estates in Massachusetts are administered using one of three different procedures depending on their size and complexity. Small probate estates can often be administered with a minimum of court supervision using the Voluntary Administration rules. Larger estates must petition the Probate Court to use either the Formal Administration rules or the Informal Administration rules, depending on the degree to which interested parties will need the probate court to adjudicate unknown or disputed issues concerning the estate. No matter which type of administration an estate uses, the rights of creditors are limited, so even relatively small creditor claims may be worth discussion with an attorney.

Voluntary Administration, available for probate estates with a car and additional assets valued at $25,000 or less, requires the submission of a few forms and a fee of $115. Once accepted by the probate court the Voluntary Personal Representative has limited authority to receive payments, deliver assets, and discharge liabilities with a minimum of court supervision through Voluntary Administration rules.

Informal Administration generally begins with notice to interested parties, a petition to appoint a Personal Representative (“PR”, formerly Executor), the filing of a packet of forms and payment of a $390 fee. The PR can then administer the estate in accordance with the will, or if there is none, the rules of intestate succession, without direct supervision of the probate court. Informal Administration can be very efficient when administration is routine and the interested parties are in agreement. If a party objects to some aspect of the probate or there are disputes about the estate, Formal Administration provides a process wherein the probate court adjudicates disputes regarding the estate.

Formal probate matters are typically heard by a judge and may involve one or more hearings before the court. Unlike informal probate, in a formal proceeding the court officially determines the decedent’s domicile at death, the heirs of the estate, and the status of testacy, i.e., whether a decedent left a valid will or died intestate. There are a whole host of problems that can require Formal Administration. Aside from addressing disputes that arise from Informal Administrations, many cases begin under Formal Administration when, for example:

-

- the original will has handwritten words added or crossed out;

- there is no official death certificate;

- the location or identity of any heir at law or devisee is unknown;

- the person to be appointed PR does not have priority for appointment by statute or by renunciation and/or nomination;

- an heir at law or a devisee, is an incapacitated person, a protected person, or a minor and is not represented by a conservator, or is only represented by a guardian who is also the petitioner.

As a result, Formal Administration is generally longer, more complicated and more expensive than Informal Administration.

If you, or someone you know is administering the estate of a loved one, please contact me to help optimize the efficiency of administration and the value of bequests to beneficiaries. A short conversation may make a big difference.